Sustaining Sustainability

Texto por Alexander Horne

Oslo, Noruega

15.01.10

Following the recent Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, what chance is there of the sustainability agenda in architecture actually being delivered?

Sustainable Pie, illustration by Alexander Horne, 2009

'To be taught to write or speak – but what is the use of speaking if you have nothing to say? To be taught to think – nay, what is the use of being able to think, if you have nothing to think of? But to be taught to see is to gain word and thought at once, and both are true.' *1

Towards the tail end of the Nineties and through to the Noughties, many of us became acquainted with a consumer term known as 'green-washing', a technique that increases an object's perceived value (usually food) by tailoring a product storyline to include some 'green' environmental benefit. *2 Evidence of green-washing could be seen most visibly in supermarkets, where, for example, a basic in-house brand of coffee would suddenly find itself labelled with exotic sales text such as 100% organic, fresh, green or ethically produced, and often with a picture of its supposed origin or maker.

Perhaps supermarkets were doing us a favour by letting us know where they sourced their food from and how good it was for the environment, the more we bought from them. Sadly, the truth in too many cases was that, behind the interesting product storylines, shops could be found selling the same products as before. There were even reports of large chains bullying the very suppliers they were celebrating on their product packaging, with threats of taking their business elsewhere if the price was not lowered, knowing that the supplier relied on a steady income from such a large customer.

As the sun sets on the Noughties, a new 'green' watchword has entered the public's vocabulary, with a supposedly deeper meaning than those green-washing one-liners we have become familiar with on our local supermarket's washing-up liquid and coffee beans.

Sustainability, not a particularly new term for architects or designers, had generally not been the most popular in the dictionary until recently. In the last century, however, several prominent creative minds were working with ideas that we would now describe as 'sustainable'. Victor Papanek, a man who some say has been more quoted in the last six months than during his entire lifetime, *3 lectured and wrote passionately about his quest for honest and function-led design for everyone, as opposed to aesthetically oriented objects, which are sold to line the pockets of the few.

Papanek's two most notable publications, The Green Imperative: Natural Design for the Real World (1995) and Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change (1971), are currently enjoying a dusting-down by product-design and architecture students who had been introduced to his work by professors or their peers. Another much celebrated and pioneering figure of the past that aspired to design for the good of humanity was the inventor / designer / futurist Buckminster Fuller. Perhaps most famed for his lattice-shell structures, whose influence can be seen in Nicholas Grimshaw's Eden Project in Cornwall, England, among others, or for his failed Dymaxion car project, Fuller strived to create and explore the new in the hope of having a positive effect on the long-term future of humanity. *4

Fuller researched, developed and shared opinion on energy and material efficiency in design and architecture, often speaking negatively about the effects and cost on the environment of driving a car in the city, something that is still debated today.

In Luce, design by Positive Flow for So Watt! exhibition, www.positiveflow.net, 2008

In 1997, a general concern about the environment and the need for a reduction of four greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and sulphur hexafluoride) resulted in an agreement we know as the Kyoto Protocol. However, many of the world's major nations, such as the United States of America, weren't in agreement and refused to sign the document out of concern with their own home economies. Those countries that did participate managed to achieve their reduction targets for energy use, but, there again, energy is only one aspect of sustainability.

Sustainability, in turn, is not just a niche concern; it is a general term for many methods of environmentally responsive action. Important to know, energy use is relatively easy to quantify. Thought-provoking exhibitions such as So Watt! and forthcoming legislation changes that will effectively lead to the phasing out of filament lamps in favour of LEDs are positive contributions.*5

A wider holistic view, however, should take in such aspects as which materials are used, how they are used, and how the building or product is used now and will be used in the future. Combining these issues should really mobilise the term 'sustainability'. Merely dealing with one sustainability issue would short-change a serious global and local concern.

The end of 2009 once again saw world leaders meeting to discuss, as they had at Kyoto, climate change, the reduction of harmful emissions and sustainable solutions. This time the venue was Copenhagen, and the run up to the event fostered a great amount of hope for, and belief in, the possibility that there would be significant changes agreed upon to protect the environment. The result, unfortunately, was that although some further minor reduction targets were set with regard to energy and emission, there was no evidence of a general consensus or rating system that all nations have to follow.

Forcing architects and designers to reduce the energy used in construction or during the lifetime

of a building / product would be effective if there were more guidance that took into consideration the other sustainability issues already mentioned (building use and material selection). This current lack has allowed the adjective 'sustainable' to be used freely, whether it be in relation to a project, material, certification, book or brand.

As a result, design-consultancy services have appeared that offer to cover these unrated issues, giving a company or project a green and sustainable finish. Material libraries, certifications and consultancy services, such as Grow Me The Money, are being allowed to work freely without the same energy-related constraints their architect and designer clients face. *6

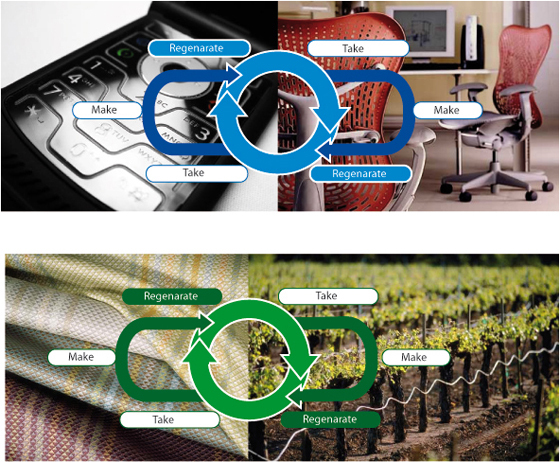

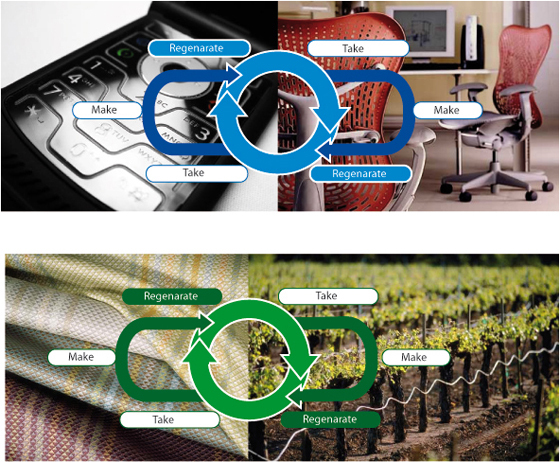

Two of the most respected and well-known of these services in the Nordic countries – Miljøfyrtårn and Cradle to Cradle – attempt to evaluate and determine the creative process from beginning to end, as opposed to jumping into projects and freely handing out sustainability tags. While Miljøfyrtårn rates small-to-medium-sized companies in Norway (shops, curtain makers and architects, for example) with a more holistic overview, the Cradle to Cradle certification is a more project-specific and is awarded globally.

To be graded by Miljøfyrtårn, companies must first apply through their local municipality (kommune) before paying for a licence and being allocated a consultant who will examine everything from a company's recycling habits to whether staff cycle to work and turn the lights off at night. To date, they have rated 2,051 companies, organisations and businesses in Norway, and are working with the Nordic Cooperation to expand their activity to further areas in Scandinavia and to similar programmes.

Although discussed and referenced frequently in architectural and design debate of late, so far only one Cradle to Cradle-certified studio has operated in Norway – 2025 design in Trondheim. To achieve certification and grading, companies must submit projects that consider materials, recyclability, energy efficiency, efficient use of water, and also demonstrate that they have implemented strategies for social responsibility. If a nominated product meets the necessary criteria, it will then be graded as either Basic, Silver, Gold or Platinum, and can be branded as 'Cradle to Cradle Certified'.

Cradle to Cradle Design, illustration from Norsk Designrad, www.norskdesign.no, 2009

Both the Miljøfyrtårn and Cradle to Cradle sustainability certifications appear to be going in the right direction but why are they not being promoted as much as other energy initiatives and pieces of legislation are? One way of addressing this, which comes from Architecture for Humanity co-founder and executive director Cameron Sinclair and could lead to a combined solution, is the return of pattern books. *7

Pattern books have been mentioned recently in relation to self-build homes and volume housing, a revival of those reference guides that ensured 19th-century builders could endlessly replicate attractively designed houses. In the case of Architecture for Humanity, a charitable organisation that promotes

architecture and design solutions to humanitarian crises

and provides design services to communities in need, Sinclair suggests that these informative guide books be made available to locals who do not have sufficient construction knowledge or access to help, in the same way the 'When there is no doctor' series of books do medically in certain parts of Africa and Asia.

Instead of being a process guide that aims to put knowledge in someone's hands other than the architect, could this exchange of knowledge not be reversed in order to give an architect or designer greater choice and control over their actions through a universal benchmark for sustainability? Sometimes even the greatest visionaries need to be taught how to see.

Eden, Multiple Greenhouse Complex by Nicolas Grimshaw

Footnotes:

*1

See Selected Writings by John Ruskin, Oxford University Press, 2009.

*2

See 'About Greenwashing' on www.greenwashingindex.com, EnviroMedia Social Marketing.

*3

See comment by Emily Campbell on RSA Design & Society blog, 23 April 2009, designandsociety.rsablogs.org.uk.

*4

The Dymaxion concept car transported more people and used less fuel than conventional cars. The project stopped abruptly, however, after the death of a test driver at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair.

*5

So Watt! was an exhibition from France featuring design solutions for more economical use of electricity; curated by Stéphane Villard, EDF Design in partnership with Cité du Design, 2008.

*6

A 12-month online programme that aims to make small-to-medium sized businesses become

sustainable and to save money. See www.growmethemoney.com.au.