Lost Space found - Architecture with a Story

Text by NoéMie Schwaller

Zürich, Switzerland

05.03.09

How can you translate literature into architecture – and how is architecture manifested in literature?

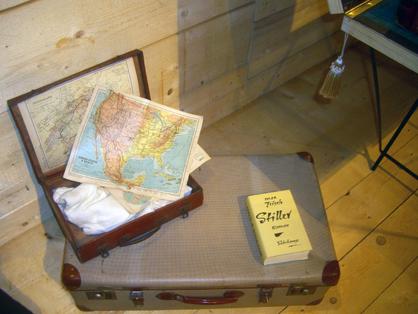

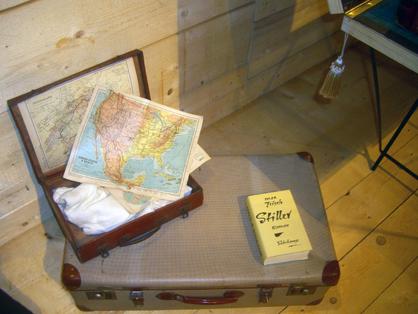

On the basis of the writings of Max Frisch, in particular his novel «Stiller», the London-based architect Markus Seifermann (Studio ’Patalab) has created an installation which forms a bridge between literature and architecture. With its search for a lost identity the spatial approach to Max Frisch's «Stiller» picks up on a central motif in the novel and revisits it in an original manner. The installation was organised in collaboration with the Max Frisch Archive at the ETH Zurich.

«The Lost Space of Stiller», organised by the Max Frisch Archive in the main hall of the ETH Zurich.

«The Lost Space of Stiller», organised by the Max Frisch Archive in the main hall of the ETH Zurich.

×It is the architect's dilemma to have to deal with incidentals in order to achieve the real objective. The real objective is the space in which the life of its occupants unfolds and which is involved in a constant process of change. The architect, however, works on material and static elements. As a result the designer shares the fate of the writer: «The important thing is the ineffable – the white space between the words...», as Frisch once wrote. This is exactly what Seifermann's installation takes as its subject: the focus is not on the objects which are individually exhibited but on what happens as the result of their combination in space, explains Seifermann. He also refers to this as the «magical moment» – a feeling of happiness which good architecture can inspire in people by the design of the spaces they live in. The technique of the collage and the 'ready made' as it is used here is in direct relationship with Frisch's own literary approach. In stories such as «Man in the Holocene» he also wove outside texts like a collage into the story of his protagonists.

In search of the ineffable – a collection of clues.

Seifermann has set up free associations with the novel in three outsize wooden freight containers grouped around a scene resembling a living room, with a couch, TV, carpet and chandelier. This mobile 'apartment' is the home of the imagined figure of the «identity stalker». He collects clues to Stiller's putative identity, which he plans to compile into a whole – a project which is doomed to failure. In a museum-like bathroom in a container, for example, a number of suspended razors hum an electrifying, repetitive rhythm. In a glass case opposite there are glass bowls with landscapes made up of whiskers – a «shaving diary», as the accompanying text explains. A projection in the dining room shows Zurich buildings where people by the name of Stiller live. From one corner of the hall fragments of conversation flow upwards from a number of gramophone horns, while in the third container six dummy torsos are suspended on meat hooks over a long table containing meat grinders. In the installation film, objets trouvés, sounds and images merge into a partly buoyant, partly threatening overall work of art, with the name 'Stiller' becoming a universal metaphor for a disowned identity. What we look for in vain here is texts – the architect wanted to remain true to his chosen mode of expression. He has allocated a function to the various spaces and furnished them accordingly, but without allowing them to be influenced by the design or the location of the imposing main hall of the ETH.

Torsos and meat grinders as part of the installation «The Lost Space of Stiller». Photo: S. Schläfli/ETH Zurich

Torsos and meat grinders as part of the installation «The Lost Space of Stiller». Photo: S. Schläfli/ETH Zurich

×From 1936 to 1940 Max Frisch studied architecture at the ETH Zurich. In the subsequent 14 years of his 'second job' as an architect he may only have designed four buildings, with the biggest of them the 'Landistil' open-air pool in Letzigraben which was opened in 1949 and for which Frisch won the first prize of 3000 Swiss francs in an architectural competition organised by the city of Zurich. In spite of this limited output Frisch remained interested in architecture and space for the whole of his life – whether in the form of concrete buildings or in the imagination as expressed by his stories.

Those who know the novel 'Stiller' and look for direct references to its contents will probably be disappointed by the installation. The only reflection of a theme which runs through Frisch's novels is the search for a person. In his work Seifermann is not aiming at a visual presentation or a re-creation of the book, as he explained at the opening of the installation. The architect has stated that the initial, ostensible level of locations such as the sanatorium or the prison cell which are described in the book only interest him to a limited extent. He is much more interested in the second level, involving the spaces which open up between the people in Frisch's book – for example between the main protagonists Stiller and Julika. This second level may not be immediately accessible to every visitor to the installation, but if you respond to the surroundings you can't help getting a feeling for Stiller's hopeless search for an identity, or Homo Faber's struggle with himself – even if it's only as a result, for example, of the soul-destroying, never-ending turning of a wax gramophone record which sounds like a thunderstorm coming ever closer.

In the area of our cultural heritage, in particular the visual arts, the relationship between light and its surroundings is a complex subject for research, involving the use, preservation and interpretation of the specific works. The Italian manufacturer iGuzzini has dedicated itself to researching these connections and in 1998 received the Guggenheim prize for its many and varied cultural activities at the local and national level.

As official sponsor iGuzzini Switzerland not only planned and implemented the lighting for the installation but also illuminated the dome of the ETH from the outside for the duration of the exhibition. For the entrance hall 18 Cestello standard lamps on two levels were selected, which enables the normal lighting conditions to be controlled simply and flexibly. In the installation's dining room, where the projections on the table have to be taken into consideration, dimmable LED Express built-in spots are used, each of which is aimed at the most significant objects in the room. A fluorescent tube of 6500 degrees Kelvin creates a cold and aseptic atmosphere in the bathroom. The outside illumination highlights the window areas of the dome with Linealuce and Woody lamps, which are alternately fitted with hot and cold discharge tubes and fluorescence. The facade is lit by Maxiwoody, also with discharge lamps.