Prefabricated Architecture

Text by Alyn Griffiths

London, United Kingdom

24.07.12

When architects such as Jean Prouvé and Charles Eames began experimenting with buildings made using off-the-shelf components following the second World War, little did they know that technology would one day allow buildings to be created from kits cut by a computer anywhere in the world. Architonic looks at some of the more radical examples of contemporary prefabricated architecture, and the materials and technologies making these possible.

A pile of prefabricated concrete beams form the structure of Antón García- Abril’s Hemeroscopium house Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

A pile of prefabricated concrete beams form the structure of Antón García- Abril’s Hemeroscopium house Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

×The basic premise behind prefabricated construction is the ability to manufacture the parts needed to create a building offsite and then assemble them swiftly, reducing the amount of labour required. There are many different methods and materials that can be used to achieve this aim and digital technologies and modern engineering have opened up new opportunities in this area.

When Spanish architect Antón García- Abril of Ensamble Studio decided to build a house for himself and his family on the outskirts of Madrid, he chose to showcase the structural potential of prefabricated concrete beams with a design that balances 230 tonnes of concrete and a steel frame in a seemingly unstable arrangement. Three massive I-beams form a helical foundation upon which the other sections are balanced and a twenty tonne chunk of granite perched atop the uppermost beam acts as a counterbalance for the entire structure.

A huge granite slab, which the architects wryly refer to as ‘the G-point,’ acts as a visual expression of the gravitational forces holding the structure together Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

A huge granite slab, which the architects wryly refer to as ‘the G-point,’ acts as a visual expression of the gravitational forces holding the structure together Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

×Due to the complexity of the loads on each of the joints and the prestress and post-tension that the beams are subject to, calculating the statics for the house took an entire year. In total, the building was three years in the planning, but once the components were delivered to the site it took just seven days to crane the separate elements into position.

Extensive glazing contrasts with the raw monumentality of the concrete components Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

Extensive glazing contrasts with the raw monumentality of the concrete components Antón García- Abril 2008 Photo: courtesy Ensamble Studio

×The 2.5 metre height of the beams determines the ceiling height within the building, which is wrapped in glass, creating a contrast with the solidity of the concrete. Ground floor living spaces surround an open but sheltered courtyard, while the bedrooms are located upstairs where there is also access to another of the building’s unique flourishes – a pool contained within the channel of a twenty metre beam that juts out over the garden. The extraordinary construction and aesthetic represents an experiment into the extremes to which prefabricated materials can be taken and results in a building that is part home, part sculpture.

Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy’s SIP Panel House is built entirely from structural insulated panels Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy’s SIP Panel House is built entirely from structural insulated panels Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

×More conventional methods of creating homes using prefabricated components involve manufacturing standardised parts in a factory and then transporting these to the site where they are assembled. Structural insulated panels (SIPS) are a popular option as they offer excellent load-bearing and thermal characteristics. The pre-engineered panels are made from two surfaces of oriented strand board sandwiching a core of injected foam insulation.

In an attempt to explore the simplest possible way of working with SIPS, architects Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy designed the SIP Panel House around a modular system of standardised wall and floor panels. The panels are configured in a staggered arrangement to create a two storey building made up of volumes of different dimensions that match their functions.

Internal dimensions are based on multiples of the wall panel’s width Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

Internal dimensions are based on multiples of the wall panel’s width Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

×Located in Santo Domingo, Chile the main living spaces are clustered towards the north end of the building to make the most of the sea views, while sections of the second storey are left open to provide large terraces and balconies. The house’s western facade features extensive glazing, while the eastern facade facing a neighbour’s property presents a more closed aspect.

The 71 wall panels and 40 split-level panels that form the building were put together in just ten days, creating a prototypical house that embodies the architects’ idea that standardised elements made from this autonomous and easily assembled material can still be used to create homes of differing dimensions and character.

Only two sizes of panels were used in the house: wall panels measuring 122 x 244 x 11.4 mm, and split-level panels measuring 122 x 488 x 21 mm Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

Only two sizes of panels were used in the house: wall panels measuring 122 x 244 x 11.4 mm, and split-level panels measuring 122 x 488 x 21 mm Alejandro Soffia and Gabriel Rudolphy 2011 Photographer: Felipe Fontecilla

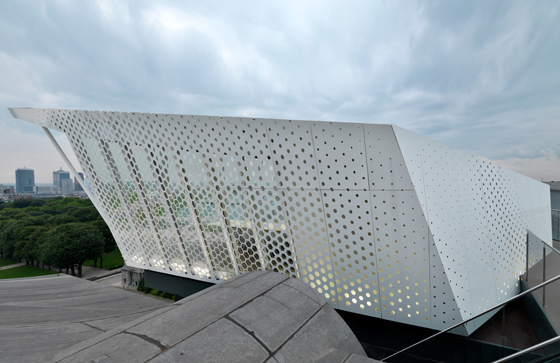

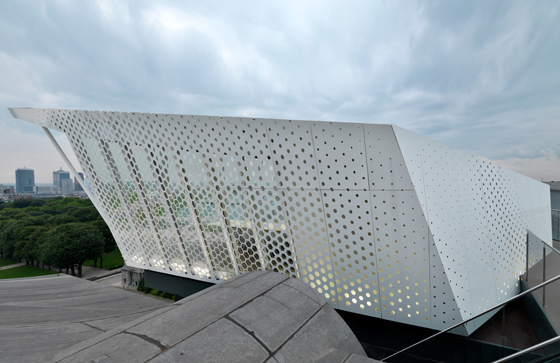

×In contemporary urban environments where space is at a premium rooftops can offer the possibility for vertical expansion, and in this scenario prefabricated building methods excel as the readymade pieces can simply be craned into place with no additional foundations required. This was the approach taken by Dutch practice Benthem Crouwel Architekten when designing a penthouse to sit atop their renovation of a former shipbuilders workshop on Rotterdam’s Wilhelminapier peninsula.

The main building now houses 25,000 square metres of multifunctional space, including the Dutch Museum of Photography, but it is the spaceship-like extension that seems to hover above its rooftop that attracts most people’s attention. It sits on 23 steel support columns that had to be carefully positioned around the existing chimneys, beams, windows and staircases on the building’s roof and is built from lightweight materials – including hollow-core concrete floor slabs – to minimise additional load on the overall foundations.

Benthem Crouwel’s extension to the Las Palmas building in Rotterdam looks out over the surrounding docklands Benthem Crouwel Architekten 2008 Photograph: Jannes Linders

Benthem Crouwel’s extension to the Las Palmas building in Rotterdam looks out over the surrounding docklands Benthem Crouwel Architekten 2008 Photograph: Jannes Linders

×All the elements used to construct the penthouse were delivered to the site on trucks and hoisted onto the roof, where they were assembled around an aluminium substructure. Ninety percent of the building’s volume is contained in a simple cuboid, but at either end the floor curves up to become the walls and then the roof, creating a continuous loop that evokes the curved bows of the ships in the surrounding docks. Aluminium panels wrap around the building and are covered in a robust coating to help withstand the corrosive maritime air.

The penthouse perches on top of a renovated shipbuilders workshop, originally designed in 1953 Benthem Crouwel Architekten 2008 Photograph: Jannes Linders

The penthouse perches on top of a renovated shipbuilders workshop, originally designed in 1953 Benthem Crouwel Architekten 2008 Photograph: Jannes Linders

×The penthouse contains the headquarters of a real estate developer and most of the two-storey interior functions as flexible office space, with a double height boardroom and four smaller meeting rooms occupying the northeast corner. Internal walls and ceilings are clad in the same material used for the building’s exterior, with wood, ceramic and stone softening the aesthetic. The prefabricated penthouse adds an additional ten percent to the renovated building’s volume, but more importantly its gleaming parasitic presence acts as a beacon for this docklands development.

Inside the double-height boardroom Benthem Crouwel Architekten 2008 Photograph: Jannes Linders

If required, prefabricated structures can be designed to be assembled and disassembled at a speed that makes them particularly suitable for temporary uses and transportation to different venues. The Cube is a nomadic restaurant designed by Italian practice Park Associati for Swedish electronics company Electrolux. It first appeared on top of the Parc du Cinquantenaire monument in Brussels, Belgium and has since been touring European cities, popping up in eye-catching locations.

The Cube is an itinerant restaurant designed by Italian architects Park Associati for Electrolux. Seen here at the Royal Festival Hall in London Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

The Cube is an itinerant restaurant designed by Italian architects Park Associati for Electrolux. Seen here at the Royal Festival Hall in London Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

×It takes a team of 18 staff nine days to assemble the Cube when it arrives in a new city, and five days to deconstruct and prepare it for transportation to the next location. Materials were selected for their robustness, as they must withstand the stresses of transit and the diverse climatic conditions to which they could be exposed. An aluminium skin sheaths the exterior and features a geometric laser-cut pattern that ties in with the building’s faceted form and regulates the level of light entering and emanating from the interior.

An aluminium surface with laser-cut pattern wraps around the restaurant’s faceted exterior Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

An aluminium surface with laser-cut pattern wraps around the restaurant’s faceted exterior Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

×The Cube’s 140 square metre floor space includes a 50 square metre external balcony where guests can gather before sitting down to dinner in an interior inspired by Electrolux’s Scandinavian heritage. A combination of hardwearing materials including Corian and lacquered wood create a pristine white backdrop, accentuated by furniture from Driade and warmed by a wooden floor, a carpet from Swedish brand Kasthall, and adjustable ambient lighting. Diners can watch the chefs at work in the open kitchen and, once the meal is over, the table can be raised out of sight creating a more relaxing environment. For such a small building, The Cube brings together several smart ideas and shows that prefabricated construction can provide suitable pop-up venues for premium experiences.

The Cube has been travelling to different European cities. It is assembled from prefabricated parts, stays for three months and is then disassembled before moving on Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

The Cube has been travelling to different European cities. It is assembled from prefabricated parts, stays for three months and is then disassembled before moving on Park Associati 2011 Photographer: Andrea Martiradonna

×Taking the principle of easy-to-assemble prefabricated building techniques to the next level, the WikiHouse is a concept for self-build homes based on downloadable templates informed by the rise of customisable software and the accessibility of digitised manufacturing methods such as 3-D printing and laser etching. London-based creative studio 00:/ designed various templates for kits that can be downloaded using open-source software and cut from standard plywood sheets by anyone with access to a computer-controlled milling machine.

Users also download instructions of how to assemble the different kits, which require no additional building equipment 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

Users also download instructions of how to assemble the different kits, which require no additional building equipment 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

×The kits are then assembled to form a frame in a process that requires no additional tools or previous building experience. The pieces slot together like a jigsaw puzzle, forming a framework that can then be clad, insulated and plugged into available services.

WikiHouse is an ongoing experiment and its creators invite anyone with an interest in making housing available on a mass scale to engage with the project through an expanding online community where new designs can be added, improvements suggested and more developed hardware or software solutions plugged in to create an evolving ecosystem around the core principle of freely available, affordable and sustainable construction.

The WikiHouse is assembled from a kit that can be downloaded and cut from plywood sheets using a CNC milling machine 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

The WikiHouse is assembled from a kit that can be downloaded and cut from plywood sheets using a CNC milling machine 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

×Having presented prototypical examples at fairs including the Gwangju Design Biennale in South Korea and the Milan furniture fair, the designers are developing the product for use in disaster relief scenarios, where the speed of assembly and possibility to use locally sourced materials could be hugely beneficial. This is prefabrication taken to new extremes, but in the internet age, why shouldn’t we be downloading buildings as well as everything else?

A computer-controlled milling machine cuts sections for the frames from standard sheets of locally available material 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

A computer-controlled milling machine cuts sections for the frames from standard sheets of locally available material 00:/ ongoing Photo courtesy 00:/

×