Architecture/New Models: Diébédo Francis Kéré

Text by TLmag

Brussels, Belgium

09.07.18

Diébédo Francis Kéré creates places of community.

Diébédo Francis Kéré Photo: © courtesy of Erik Ouwerkerk

The work of Diébédo Francis Kéré goes beyond the accumulation of glass, steel and bricks. The Burkina-Faso-born architect conceives buildings with local materials and open structures that correspond to the climate conditions of the African continent. That his design principles also apply to moderate climate zones, was revealed his 2017 pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery in London.

Serpentine Pavilion Photo: courtesy of Kéré Architecture

Architecture centres around boundaries. Inside and outside spaces are divided by walls, windows and roofs. Floors are separated from each other by ceilings and fragmented into smaller units by inner walls and doors. Like a counterpart to that approach seems the work of Diébédo Francis Kéré. He favours openness and connectivity instead of spatial isolation. “Coming from a continent like Africa, I am accustomed to being confronted with climate and natural landscape as a harsh reality," says the architect.

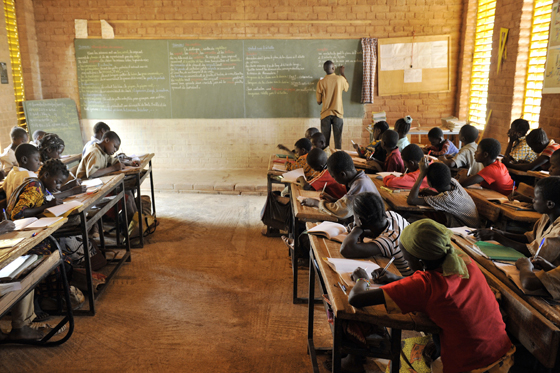

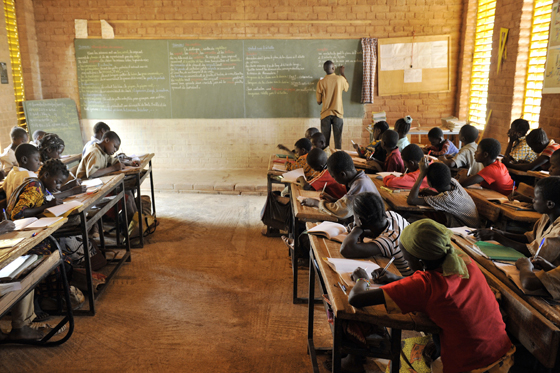

He was the first child in his native village Gando to attend school. At the age of seven he moved to the city and lived with his uncle. Later, he became a carpenter and received a scholarship to study architecture at Berlin's Technical University. During that time, he initiated an association to fund a primary school for his village. The building became his graduate project and right after its completion in 2004, Kéré founded his own architecture firm in Berlin.

Interior Hando Library (top); Gando, Burkina Faso (above) Photos: courtesy of Kéré Architecture

The school in Gando set the agenda for improved construction principles that correspond with the specifics of the site. Kéré declined to work with concrete, which is normally used for school buildings in Burkina Faso. The material heats-up too fast and also requires high sums of energy during the building process – an inevitable aspect when the entire village is off the grid. Instead the young architect used mud bricks that were manufactured on site and pursued the local building traditions.

Gando Primary School (top); Grando Primary School, Front (above) Photos: © courtesy of Erik Ouwerkerk

Gando Primary School (top); Grando Primary School, Front (above) Photos: © courtesy of Erik Ouwerkerk

×In addition, a cantilevered roof and open walls allow the air to flow. The consequence is a natural, nonelectric cooling system that works perfectly in an area where temperatures easily rise up to 45 degrees Celsius. "My experience of growing up in a remote desert village has instilled a strong awareness of the social, sustainable, and cultural implications of design. I believe that architecture has the power to unite and inspire while mediating important aspects such as community, ecology and economy," says Francis Kéré.

Serpentine Pavilion Photos: courtesy of Kéré Architecture

In 2017 he designed the annual garden pavilion of the Serpentine Gallery in London. The sense of openness was also fundamental to this temporary building. It had four different entry points that led into an open air courtyard, where visitors could sit and relax. The cantilevered roof acted as solar protection and an illuminated screen by night. An oculus in the middle of the roof embraced British weather in an unexpected manner. In case of rain, water was collected by the roof structure and funnelled downwards as a dramatic cascade before being evacuated by a drainage system in the floor.

"In my culture, certain trees hold spiritual meaning and mark important points of gathering and decision-making for the community. Like a tree, this pavilion offered protection from the sun but still allowed you to experience wind and rain," explains Francis Kéré. As a consequence, the notion of inside and outside disappears. An open, inviting, yet protecting structure for social encounters that reinforces the sensuality of nature: aspects that go far beyond square meter numbers and investor aesthetics, giving the building process a pleasant human side.

Text by Norman Kietzmann