Teilen

Strap

Teilen

- Startseite/Regale/

Strap

Über dieses Produkt

Architonic ID: 1114117

Einführungsjahr: 2000

Konzept

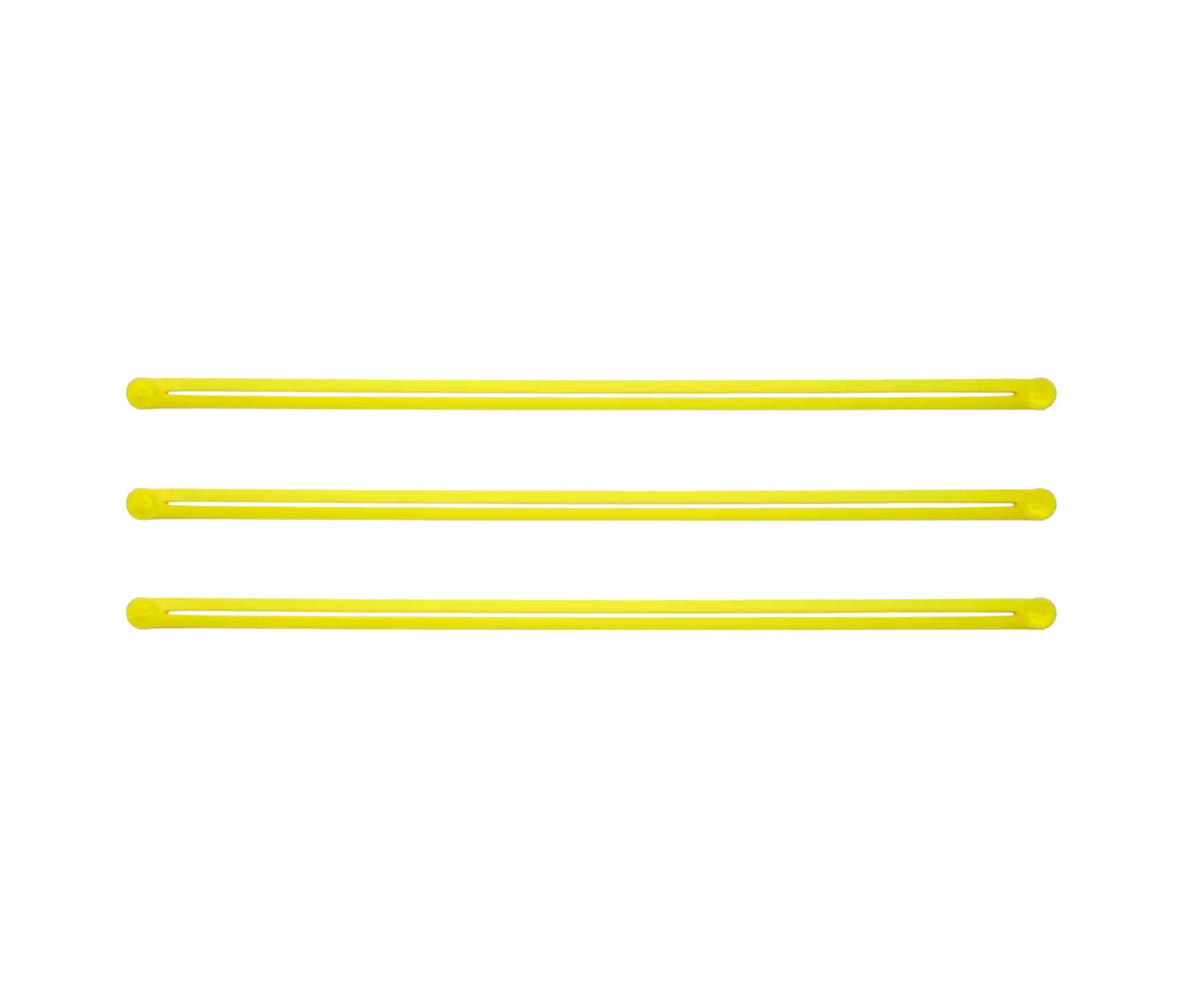

A bike strap to be fixed onto the wall. A nice way of storing books, magazines, toys and other objects.

Material: silicone rubber, (includes wall fixture), max. stretch 90cm

Colour: antracite, white, red, green, blue, fluro yellow

Size: 72 x 3 x 1 cm / 28.3” x 1.2” x 0.4”

Dieses Produkt gehört zur Kollektion:

Zeitschriftenregale, Schuhregale, Wandregale / Ablagen

Objektbereich, Büro, Wohnen

Netherlands

The Remix NL Architects is an Amsterdam based office. The initial four principals, Pieter Bannenberg, Walter van Dijk, Kamiel Klaasse and Mark Linnemann, officially opened practice in January 1997, but have shared workspace already since the early nineties. Architecture is the medium through which we hope to contribute to the understanding of contemporary culture -and to its development. We understand architecture as the speculative process of investigating, revealing and reconfiguring the wonderful complexities of the world we live in. Can we compress banality into beauty; squeeze the sublime out of the obvious? How can we transform, twist, bend, stack or stretch, enhance or reduce, or reassemble the components that constitute our environment into new and better configurations? We were all educated at Delft University while living in Amsterdam. As a consequence we have spent a lot of time in the confined space of the car, about two hours a day. The conversations and the exchange of ideas were inspiring. In that sense we like to think of ourselves as auto-didactic; the recurrent fascination with mobility and tarmac perhaps could be traced back to being ‘educated’ on the highway. (Traffic jams would mean longer time to ‘study’). The first office space was a blue metallic Ford Escort Station. The use of the Dutch bumper sticker as a Logo can be explained from this origin. .NL is the Internet extension for the Netherlands -adding the dot to the bumper sticker expressed the emerging love for the Digital Highway too. The insertion of the point was the minimum addition that allowed appropriation of the already existing emblem. As such the logo serves as a reminder: can we do it with less? This ambition to alter ‘The Existing’ by modifying as few parameters as possible could maybe be considered a property of ‘Dutchness’. At least it is a fundamental part of our ‘game’. Often the projects focus on ordinary aspects of everyday life, including the unappreciated or negative, that are enhanced or twisted in order to bring to the fore the unexpected potential of the things that surround us. By sampling existing fragments of reality and recombining them, gluing bits and pieces together into new coherent arrangements, our architecture can be understood as The Remix of Reality: the architect as Deejay. The office has always operated at the level of the hypothetical and the concrete simultaneously. New media allowed us to investigate speculative realities -this is one of the great assets of growing up in the nineties- while at the same time the hands-on work for friends and family (and later professional clients) from the start gave us a sense of the tactile, of the ‘real’ assembly of materials and spaces. By reconfiguring our everyday reality we hope to establish more efficient / more practical solutions for our surroundings, and to produce more ‘meaningful’ combinations of what is ‘already there’. These ‘affective relations’ can emerge if we discover (or create) links with the context. This can either be the physical reality that envelops a project, or the set of rules and regulations or ‘culture’ that forms its backdrop. In order to be successful the work should be ‘embedded’ in more than one way. We believe that the best design is capable of resolving multiple issues in a single gesture. We can identify several recurring obsessions: ‘Publicness’, is it possible to upgrade accessibility; can we enhance the public character of a building? Doubling –not just in terms of stacking, but can we achieve multiple effects, results or meanings in one single gesture? Integrated Differentiation –can we create a series of sections / areas that have specific qualities and that are at the same time ‘unified’? An ongoing investigation is how to ‘integrate’ the car in architecture and urbanism. It is remarkable to see that the position of the car in architecture and urbanism –100 years after its invention- is not yet resolved. Several projects focus on mixing existing typologies, like parking lot and patio dwellings for instance, or street and terraced housing. RoofRoad -an assignment for 200 houses in an expansion of The Hague- is the ‘Remix’ of the typical Dutch suburb, called VINEX. The densities in VINEX are too high to successfully reward all ‘consumer wishes’, the gardens are much too small, not enough space for kids to play. Within VINEX the roads and parking consume 37% of the ground surface; more than 55% of the textures is solid: tarmac or concrete or bricks. At the same time the densities are too low to consider the condition urban. Double use of the ground might be a solution. By combining infrastructure and building, by turning the roof into the road, 25% is gained: a quarter extra space compared to the normal VINEX! This surplus space can now be used in a better way: for public or semi-public space, green or water, for playgrounds and for large gardens. Every house has a front door and two parking spaces on the roof. By positioning the driveway on top of the houses a wonderful panoramic view is guaranteed: a roof with a view. The ground level is car free and kid friendly. Although childishly simple in concept the paradigm shift proved to be too dramatic. With the decline of Dutch economy and the demise of courage and innovation, the project died prematurely. We still wonder: why basement parking is considered normal and rooftop parking utopist? A selection of our projects includes Parkhouse/Carstadt (an attempt to integrate auto-mobility and architecture), WOS 8 (a rubber clad Heat Transfer Station in Utrecht), the Mandarina Duck Store in Paris (for/with Droog Design) and the Dutch entry for the Biennale in Venice in 2000 (the so-called NL Lounge). The BasketBar (a grand café with a basketball court on the roof at the university campus of Utrecht) and the conferencecenterlunchloungelobby for insurance company Interpolis in Tilburg were completed. Recently a residence in Korea, the conversion of a school building into a cultural facility in Amsterdam, the ‘reanimation’ and reprogramming of the space under the elevated highway A8 in Koog aan de Zaan, a restaurant / residence pavilion in Amsterdam and -together with DS Landschapsarchitecten- a public square in Dordrecht were completed. At the moment we are working on ‘numerous projects in various stages of development’: several housing projects, among which a block for 200 units, 400 parking spaces and a shopping center of 10.000m2 in Amsterdam, 100 units in Rotterdam, 50 units in 16 stories in Groningen, Sport facilities for the University of Leiden and the city of Dordrecht -the sculptural façade doubles as climbing wall, and the so-called Muziek Paleis, a ‘crossover’ music hall in 3D Masterplan by Studio Herzberger, Utrecht. We are delighted to say that after 10 years of suspense Blok K in Funen Amsterdam –maybe our most significant housing project- is finally under construction. And we gave birth to a Monster: 3Vase is the bizarre but still fully functional outcome of an experiment to bring together 3 archetypal vases into one object in order to fit any bouquet. 3Vase became the 3D-sybol for the ongoing research into how to manipulate the Existing into previously unimagined realities. From the start we have always employed an international staff, currently of approximately 20 people – paradoxically the Dutch have always been a minority in the office!